The world’s media needed an expert when a massive ship blocked one of the world’s busiest trading routes in March. A love of history and a life at sea prepared Dr. Sal Mercogliano for this moment.

By Billy Liggett

There’s a moment less than two minutes into Ali Velshi’s interview with history professor and former merchant marine Dr. Sal Mercogliano about the massive ship blocking the Suez Canal where the CNBC host references the “Horn of Africa” as an alternate route for trade ships unable to get through. Mercogliano doesn’t blink.

“If you have to go that extended route, you’re talking about adding an additional 3,500 miles on a route from Singapore to Rotterdam,” he says cooly. “We’re talking about [an extra] 12 to 14 days, and most importantly, the ports that are expecting to receive these vessels are not seeing them.”

Mercogliano’s answer goes on for another minute. The interview — which has been viewed more than 33,000 times on YouTube — for another three minutes.

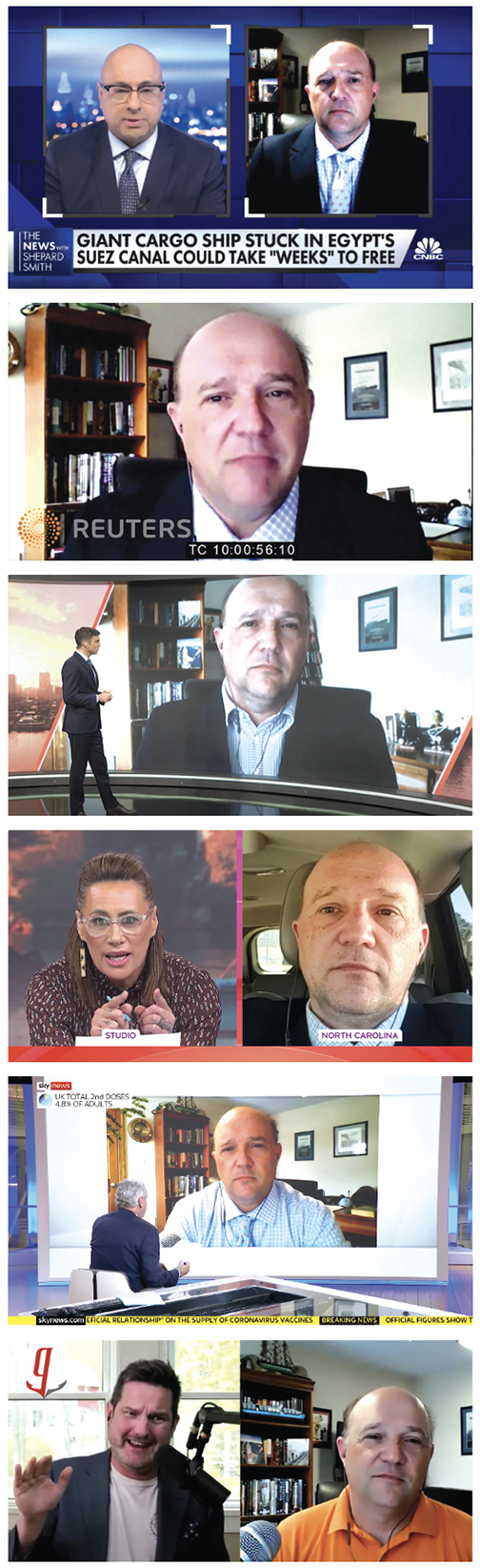

And it’s just a small sampling of what was a whirlwind month for the Campbell University associate professor of history, who also appeared on interviews with BBC, BBC International, the Associated Press, Bloomberg, NPR, CNN, Al Jazeera, Fox, ABC, Sirius XM and TV New Zealand … to name a few. Mercogliano was also quoted in articles by the New York Times, Washington Post, Reuters, the Los Angeles Times and Guardian … again, to name a few.

Mercogliano’s rise to maritime media darling might have happened overnight, but his demand was the result of a lifelong love of water and the mysteries of the deep and a lifetime of study and research of civilization’s history at sea. And when the Suez Canal — Egypt’s 152-year-old man-made waterway connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea — was blocked by the massive Ever Given container ship for six days in March shutting down one of the world’s busiest trade routes and preventing nearly $10 billion worth of goods from getting to their destinations, the world needed answers.

And few could provide them as well as Mercogliano.

“I think I bring a passion to this subject, and people seem to like it,” he says. “[The media] wanted somebody enthusiastic and knowledgeable on this subject.

“And certainly, I’m both.”

THE YOUNG MAN AND THE SEA

That enthusiasm and knowledge came early in Mercogliano’s life, growing up along the south shore of Long Island in Massapequa, New York. His family lived “right on the water,” he says, and his father’s passion was fishing on his 30-foot boat.

“That’s what he loved to do,” Mercogliano recalls. “On weekends, he and his buddies would go out, and I’d tag along, and we’d go 50 to 100 miles out into the Atlantic and fish. By the time I was 12, I was driving the boat. They’d let me drive it out, I would troll the boat, and I would run it back in.

“And when you’re that far out, you see the ships coming in and out of New York City, and I always loved that. That was for me. I just loved the idea of one day being on those ships.”

Mercogliano held onto that dream through high school and to the doorsteps of the Naval Academy after graduation. He was dealt a crushing blow during his final physical when he was told his eyesight was “so bad,” he could never be the one thing he wanted to be — a surface warfare officer. Those are the sailors who operate the most advanced fleet of ships in the world.

“The Navy pretty much told me I couldn’t drive the ships,” he recalls. “I could still become a limited duty officer, but I couldn’t do the one thing I wanted. It crushed me. I hadn’t applied anywhere else after high school. I had thought I was all set.”

There was an alternative. Mercogliano knew a young woman at the time whose brother attended the SUNY Maritime College, one of six state maritime academies in the nation with the mission of producing licensed mariners. Mercogliano applied and got in, graduating four years later with a degree in marine transportation (he also played lacrosse there).

As a Merchant Marine — the term used for civilian mariners manning vessels and transporting goods on U.S. waters — Mercogliano got to live his dream and, ironically, soon went to work for the Navy in the early 1990s. And because Merchant Marines can be called on by the Coast Guard to assist in times of war, Mercogliano was tasked with piloting a hospital ship in the Persian Gulf.

“We actually had the Chief of Naval Operations [Admiral Frank Kelso] come on board, and he came up on the bridge — and I’m about 23 at the time — and was introduced to me by the captain,” Mercogliano says. “And he asked me why I wasn’t in the Navy, and I told him, ‘Because you wouldn’t let me in.’ So not long after that, the rule changed [on eyesight requirements]. I don’t know if I had anything to do with it, but I’d like to think I did.”

His career took him all over the world. The Caribbean, the Mediterranean, the North Sea and the Baltic. Even when he wasn’t at sea, he remained involved in the maritime industry. Mercogliano also made the decision to continue his education with the hopes of learning more about and eventually teaching about his passion. He earned his master’s degree in maritime history from East Carolina University in 1997 and his Ph.D. in military and naval history from the University of Alabama in 2004.

In 2008, he became an adjunct professor of history and engineering for the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (a position he still holds today), and in 2010, he joined Campbell University’s faculty to teach several courses in history.

If the sea is Mercogliano’s first passion, history (and teaching history) isn’t far behind. During his time on the hospital ship in the 90s, the captain had Mercogliano doing live discussions with the Navy crew about “why we were out there” and “what the ship does,” as many on board were medical personnel who hadn’t spent much time on a boat (despite being in the Navy). Mercogliano discovered that he enjoyed these discussions, particularly the teaching aspect, as his talks not only covered the technology and history of the vessels, but economics, government and even religion at times.

Maritime history goes back tens of thousands of years (recent research suggests perhaps over 100,000 years) — long before the era of the Vikings and Columbus. To this day, 90 percent of the world’s goods are transported by sea. The history is deeper than the oceans themselves, and Mercogliano has become an encyclopedia of knowledge.

“What’s fascinating is that in all these years, the basic technology [of sailing] hasn’t changed,” he says. “You can take Peter the Viking and propel him 500 years into the future onto Columbus’ boat, and he could still figure it out. You can then take Columbus and put him 500 years into the future, and maybe he couldn’t figure out a toilet, but he’d still understand a boat.”

Mercogliano never enjoyed public speaking or being in front of large groups, but he found that when the discussion revolved around ships and maritime history, he was more at ease. And he enjoyed it.

Even getting in front of television cameras — for interviews broadcast all over the world — is easier when you know what you’re talking about.

AT EASE

On March 23, a 20,000 TEU-class container ship called the Ever Given was buffeted by strong winds and wound up wedged across the waterway of the Suez Canal — its bow and stern stuck in the canal banks, blocking access for all ships behind it until it could be freed.

For six days, the ship shut down access at one of the world’s busiest trade routes — at least 369 ships were either grounded or forced to find another route. An estimated $10 billion in trade was affected.

The event made global news, and media outlets around the world were scrambling to talk to somebody with knowledge of the Suez Canal and global sea trade routes, somebody with knowledge of maritime history, somebody who could explain the economic impact of the canal’s blockage and, most importantly, somebody who was comfortable on camera and is quick on their feet when tough questions are thrown their way.

They found all of those qualities in Dr. Sal Mercogliano, an expert in maritime history, nautical archaeology and maritime industry policy.

Over the next week, Mercogliano appeared on nearly 30 national and international radio and television news programs and was quoted in dozens of foreign and national newspapers. Nearly every time, the words “Campbell University” appeared next to his name. It was not only a big moment for the professor, but a big moment for the landlocked University located 110 miles from the nearest beach.

“It was a big story,” says Mercogliano. “The Suez Canal is responsible for 12 percent of the world’s trade. It’s what we call a ‘maritime choke point,’ a topic I was already writing an essay about for the Center for International Maritime Security. The canal has been closed by ships in the past, but nothing in this scope or on this scale, because this was done by one of the largest ships in the world.”

His sudden media fame was the result of a number of factors, Mercogliano says. His background as a merchant Marine, his career in higher education, his knowledge of large sailing vessels, his knowledge of the business side of the sea trading industry — they all contributed to the demand for his insight.

But what set him apart from the hundreds of other maritime history professors or experts in the country with extensive knowledge of trade routes and the global economy?

According to Mercogliano … lacrosse.

He played lacrosse in high school. He had plans to play for the Naval Academy, but when his eyesight caused a course correction, he wound up playing at SUNY. And when he learned shortly after joining the faculty at Campbell that the University would launch a women’s lacrosse program in 2013, Mercogliano — who helped start a women’s club team at Methodist University during his stint there — wanted to be involved.

“When it started here, it was such a tiny program,” he says. “We only had enough girls to field a team, but they needed extra bodies for practice — so I’d show up, throw the ball around and serve as an extra stick when they needed one.”

Mercogliano invited assistant athletics director and “Voice of the Camels” Chris Hemeyer to speak at a Lunch and Learn program for his students that year, and Hemeyer asked him if he would be interested in providing color commentary for radio and TV broadcasts of the new program. Mercogliano was hesitant — “It’s one thing to speak to a room of students, but it’s another to go on camera and not seeing your audience’s reactions” — but he eventually agreed to do it. And he did it so well, ESPN asked him to be part of the broadcast team for a Big South lacrosse championship game (which did not include Campbell).

“I got very comfortable doing it,” he says. “Before, I was always worried about saying something wrong or worried people would think I’m terrible. After a while, you realize you did fine. And it’s not like people are judging you … they’re watching a game.”

Lacrosse put Mercogliano at ease in front of a camera. Prior to the Suez Canal incident, he’d appeared in several on-camera interviews about maritime policy or other similar (but less newsworthy) events.

“Something producers have told me over and over after these interviews, ‘You’re a natural at this.’ And I’ve had a few people tell me that I seem to be really enjoying myself through all of this, and to be honest with you, I am,” he says.

“Look, I felt terrible that 12 percent of the world’s economy was close to collapsing, but this is what I’ve studied my entire life.”

THE CALLS KEEP COMING

Harris Lake is a far cry from the ocean that inspired a life’s work. But for Mercogliano, the quiet tree-lined body of water located just 20 miles from Campbell’s main campus is the ideal spot to unload his boat and spend time with his 13-year-old son, Christopher.

It does raise the question: How does a Long Island native and lifelong mariner find happiness teaching in a town surrounded by tobacco fields, 100-plus miles from the nearest ocean?

At Campbell, he found stability. He found his port.

“During the 10 years prior to coming here, I jumped around a lot,” he says. “I had a lot of temporary positions … a lot of one-year jobs. ECU. UNC. West Point.”

Mercogliano and his wife, Kathy, were already living in Buies Creek before he joined the faculty at Campbell — Kathy was attending the law school before it moved to Raleigh in 2009, and the couple lived in the small trailer park located where the Pope Convocation Center sits today. Mercogliano served as an adjunct professor, but he was approached in 2010 to teach Western civilization and other history courses full time. Soon, the young family built a house in nearby Fuquay-Varina.

Campbell became “home.” Mercogliano immersed himself in the community outside of the classroom, not only through his work with Campbell Athletics, but as a volunteer with the Buies Creek Fire Department and by volunteering to serve on committees and other organizations.

He became popular in the classroom, too. In 2013, his colleagues honored him with the D.P. Russ Jr. and Walter S. Jones Sr. Alumni Award for Excellence in Teaching. Twice in a four-year span from 2012 to 2015, he was chosen by the student body as Professor of the Year, and in 2015, he was the recipient of the College of Arts & Sciences’ Dean’s Award for Teaching Excellence. In 2021, he was named chair of Campbell’s history department.

“It’s especially important to me to be acknowledged by both students and faculty,’’ Mercogliano said back in 2015. “I run a class that isn’t an easy class by any measure … In fact, it’s pretty tough and my students are usually challenged. But these honors vindicate [that approach] … It tells me what I’m doing is helping students and influencing them in their careers.”

Six years later — sitting in an idle boat in the middle of Harris Lake — he reveals another factor in his popularity.

“The best critique I ever got back from a student was, ‘You made me stay awake,’” he says with a laugh. “I just really like being here. You know, I’ve worked at big universities where you only know the people in your department. At Campbell, you get to know everybody across campus, and you get to be a part of the community. That’s one of the nice things about being here.”

Three months after the Ever Given incident, well into mid-June, Mercogliano was still being quoted about the story in large international publications — the most recent being a Wired UK article titled, “The Untold Story of the Big Boat that Broke the World.” He also appeared in articles about who will be the next U.S. Maritime Administration chief and an Iranian warship bringing millions of gallons of fuel to Venezuela.

The media is also turning to Mercogliano to be a consultant.

“I get calls now asking if I can recommend people on different subjects,” he says. “I got a call from Ali Velshi’s show [on CNBC] after an Indonesian submarine went down asking if I knew anybody who knows about submarines. I said, ‘Sure. Here’s a list of people to talk to.’”

Seventy-one percent of the world is made up of water, and the oceans hold 96.5 percent of it. Mercogliano has always known this, and he’s known about the impact it has on our everyday lives.

Now, he’s finally realized that there will always be a demand for somebody who can talk about that impact. And he’s finally comfortable being that person.

“It’s funny, because when the ship got pulled out, I pretty much figured my 15 minutes of fame would be over,” he says. “I knew it was fleeting, and I kept telling myself it was going away. But I’m still getting calls. It’s not going away.”